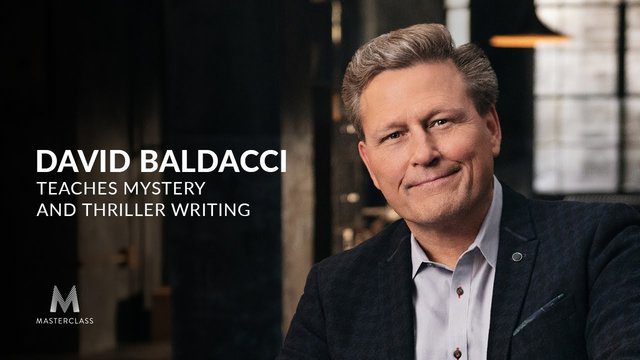

David Baldacci, the New York Times–bestselling author of 38 adult novels and 7 children’s books that have sold more than 130 million copies. His work has been translated into 45 languages, published in 80 countries, and adapted for film and television. Most of David’s novels are part of a series such as The King and Maxwell series, The Camel Club series, The John Puller series, The Will Robie series, and The Amos Decker series.

Here are my favorite take aways from viewing David Baldacci’s Masterclass Session on Mystery and Thriller Writing.:

The Writers Prism

Inspiration can come from the unlikeliest of places. Famous writers have been inspired by dreams (Stephanie Meyer), drug trips (William Burroughs), conversations (Margaret Atwood), and travel (J.K. Rowling).

Most of David’s ideas are observation-based: He has a knack for taking even the simplest or most mundane things he witnesses day-to-day and twisting them into dark, elaborate tales.

Observation is critical, so next time you leave the house, don’t be afraid to let your mind wander, link up seemingly unrelated events, speculate wildly, and take a mysterious turn. Even if it doesn’t come naturally, you can develop the ability to observe the world around you and channel your creativity into describing what you see in unexpected ways.

I think if you’re a writer, you have to be receptive to what the world gives you, and then you have to run it through your filter of creativity. Out the other end comes an original idea.

Moral Complexity

While choosing a central conflict for your story, it’s good practice to look for real-life problems that have the kind of moral complexity that will sustain an entire novel. Avoid black-and-white issues. Instead, search for situations, settings, or characters that are complicated to avoid providing readers with easy answers. Maybe certain people in the government are doing something amoral, such as hiring an assassin to kill a beloved world leader.

If the moral lines between good and bad are too easy to determine, you may find your story becoming predictable, and your readers won’t be as authentically engaged.

WRITE WHAT YOU’RE PASSIONATE ABOUT

Passion—for your story, for your subject matter, for honing your craft—is key when it comes to developing a novel. It is fuel for your writerly tank.

You don’t have to be an expert.

- Michael Crichton had a background in medicine, but his novels delved into subjects as diverse as historical crime (The Great Train Robbery, 1975), dinosaurs, and genetic science (Jurassic Park, 1990), and natural disasters (Twister, 1996). Often, topics you’re initially unfamiliar with can sustain your interest more powerfully over a longer period of time.

You can also be an expert.

- Don’t underestimate your long-term passions just because they’re so familiar to you. John le Carré was an MI6 agent for a decade before he wrote the now-classic novel The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963).

Look for multiple interests and bring them together.

- Dan Brown was interested in the Catholic Church, but he was also obsessed with code-breaking, conspiracy theories, and modern science. Putting these elements together seemed unlikely at the time, but it led to the wildly successful The Da Vinci Code (2003).

Don’t chase trends unless they’re in line with your passions.

- Mario Puzo spent years writing serious literary novels about Italian immigrants in America and became so frustrated with his lack of success that he decided to write something with blatant mainstream appeal. But he couldn’t leave his true passions behind. The result was The Godfather (1969), an unforgettable crime novel that introduced the world to the inner workings of a New York Mafia family.

Remember to let your story ideas percolate. Once you’ve written an idea down, take some time away from it—this could be a few days or weeks—and go back to it later to reevaluate.

Researching

One of the primary goals of fiction writing is to present a make-believe story that is sufficiently believable.

In the early stages of research, you’ll most likely be looking for inspiration. Use the following tips to begin building ideas for your topics, settings, and characters:

Download a research-organizing tool.

– Google Keep and Evernote both allow you to store all your materials in a handy place from the start.

Browse online for setting inspiration.

- Keep a Pinterest board of places your characters will go. Take notes on setting details from photographs online. And check out the phenomenal resources from Google Street View, which not only give you “street views” but take you into most of the world’s notable sites.

Build characters online.

- Scanning through faces is an excellent way to begin visualizing your characters. Do you think your protagonist might be a marksman? Run online searches for marksmanship competitions or famous snipers. Search YouTube for relevant content to get a sense of how your character might dress and talk. Browse through photos of actors and actresses to begin picturing your main characters in your mind.

One of the potential pitfalls of doing research is that much of what you learn will be so real that it may begin to restrict your imagination. Learning facts can set a boundary of concrete reality around your creative mind and put a damper on your more fantastical ideas.

Don’t Put Off the Actual Writing

- A good rule of thumb is to begin writing as soon as you can. Once you’ve got enough information about your characters and setting to start writing scenes—no matter how short—jot them down in your notebook.

The Pomodoro Method

- Developed in the 1990s by Italian author Francesco Cirillo, this über-simple method involves only one device: a timer. (Cirillo’s was shaped like a tomato—pomodoro in Italian.) Set your timer for 25 minutes, and write for that period only; then take a short break and start again. Breaking your workload into small tasks can be a huge productivity boost.

Gamification

- Come up with doable goals for yourself, like writing for an hour every morning, and use a goal-tracking app like Productive, Streaks, or Momentum to track your progress. Most apps will reward you for your positive streaks; the sense of accomplishment can be addictive and can motivate. you to keep going.

Your Story’s Stake

- Every story has a central conflict, or what writers call a major dramatic question. It will be tied intimately to your story’s stakes. Whenever a writer talks about the stakes of a story, they’re referring to what’s on the line for your characters. It’s the specific description of what is motivating them. Stakes are the driving force in any story, and they can be anything you want—solving a murder, apprehending a suspect on the run, falling in love—but they must feel deeply important for your main character.

- Maybe the stakes are personal: In Breaking Bad, Walter White is desperate to ensure his family’s financial security after receiving a terminal cancer diagnosis, and so he turns to making and selling meth.

It’s best to know your major dramatic question as you begin working on an outline.

The Big Pop

The Big Pop is how the novel is going to open. If you don’t get that right, it doesn’t matter what else you write after that, because nobody is going to finish reading it.

Here are some things to remember about your opening chapter:

- The events should be out of the ordinary for your character.

- Your reader should feel grounded and able to understand what’s happening. They may not know everything, but they have to know enough to comprehend the situation.

- You can mislead your reader, but don’t confuse them. Nothing will make a reader put a book down faster than feeling lost.

- As a touchstone chapter, it may be subject to change or refinement later, so keep coming back to it throughout the writing of the book.

- Keep the writing and storytelling tight: Everything on the page should be there for a reason.

The Suspense

As a suspense writer, you must always be one step ahead of your reader while subtly guiding their guesses about what’s coming down the pike. When you lead your reader down a false alley, this is called misdirection, which is a useful tool of suspense. There are a few ways to achieve this:

- Red herrings make people draw false conclusion about a situation.

- Plot twists occur when something unexpected happens in your storyline.

You want to have readers saying, ‘I never saw that one coming.‘

Recommended Books

- Writing Vivid Settings: Professional Techniques for Fiction Authors (2015) by Rayne Hall

- A Writer’s Guide to Active Setting (2016) by Mary Buckham.

- Mastering Suspense, Structure, and Plot (2016) by Jane K. Cleland.

- How Do I Conduct a Strong Interview? (2006) by Jane Friedman

- Outlining Your Novel: Map Your Way to Success (2011) by K.M. Weiland

- Outlining Your Novel Workbook: Step-by-Step Exercises for Planning Your Best Book (2014) by K.M. Weiland

About Masterclass

MasterClass is a streaming platform that makes it possible for anyone to learn from the very best. MasterClass is an online membership – accessible on your phone, web, Apple TV, Roku devices, and Amazon Fire TV – that offers classes on a wide variety of topics taught by 85+ world-class masters at the top of their fields.

Their immersive learning experiences combine incredible video content, downloadable materials, and social interaction with the MasterClass community, all of which users can explore at their own pace.

The annual membership is available for $180 USD, which allows unlimited access to ALL on demand MasterClass content for the year

David Baldacci Teaches Mystery and Thriller Writing

Give One Annual Membership. Get One Free.

MasterClass Annual Membership for only $180 USD

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

For More Information: MasterClass Home Page

1 Comment

Pingback: Lessons Learned from N. K. Jemisin’s Masterclass Session on Fantasy and Science Fiction Writing. – Lanre Dahunsi