“Narcissism, like strong drink, has its place and its purpose; it braces and emboldens and offers a wonderfully primal pleasure. Indulging in it too deeply, however, leaves you sorry and sick and wishing you’d been more moderate in your pleasures.”

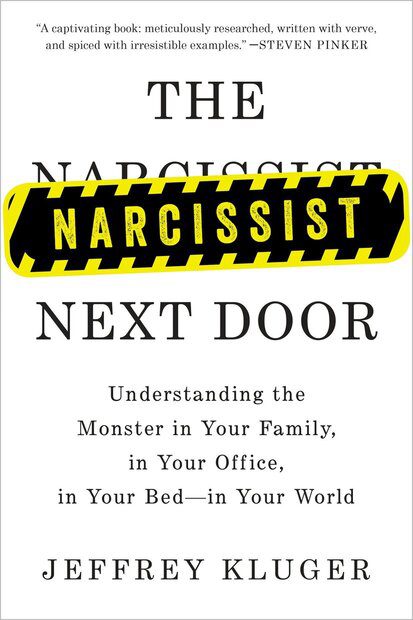

Author and senior writer at Time magazine, Jeffrey Kluger, in his illuminating book – The Narcissist Next Door writes: Narcissists are everywhere – They are politicians, entertainers, business people, your spouse, family members, friends, peers, colleagues, relationships. Recognizing and understanding them is crucial to your not being overtaken by them.

Narcissists are, in a sense, emotional muggers, people who assault their victims with a combination of stealth and misdirection—leaping out at them in situations and at times when they have a right to feel safe and taking what they want.

Narcissism, like strong drink, has its place and its purpose; it braces and emboldens and offers a wonderfully primal pleasure. Indulging in it too deeply, however, leaves you sorry and sick and wishing you’d been more moderate in your pleasures. We would feel poorer in a world without liquid spirits, just as we would without the manifold elements of the human spirit. But they are all volatile spirits. They effervesce and enliven or they singe and scald. The difference, as with so many things, is in knowing how to control them.

The Age of Narcissism

Narcissism isn’t easy, it isn’t fun, it isn’t something to be waved off as a personal shortcoming that hurts only the narcissists themselves, any more than you can look at the drunk or philanderer or compulsive gambler and not see the grief and ruin in his future.

Narcissists are corrupt public officials, and honest ones too; they are the criminals who fill the jail cells, and sometimes the police who put them there in the first place. They are in industry, in media, in finance, in show business. They are artists, designers, chefs, scholars. They are the people we work with and the people we work for; the people we love and the people we bed; the people we hire or marry or befriend, and soon want to fire or leave or unfriend. They are the people who love us—until they betray us.

Our narcissism has other expressions, too: the symbiotic exhibitionism and voyeurism of the reality show. Look at me while I, um, live in a house on the Jersey Shore, and maybe one day you can get a show and people will look at you living in a house too! Yes, there’s money to be made from being a reality star, but it’s a simple truth of commerce that the things a culture rewards are the things it values, and in twenty-first-century America, spending your life before the camera is a growth industry, with both consumers and providers willing to contribute to it.

I am special

It’s starting earlier and earlier, this pandemic of simultaneous showing off and mirror-gazing—in the everybody-gets-a-trophy ethos of the grade-school track meet, in the well-intentioned song preschoolers are taught to sing to the tune of “Frère Jacques”: “I am special, I am special, Look at me, Look at me.” Well, maybe you are, but as with the 1981 study that found that 82 percent of people believe they’re in the top 33 percent of drivers—a statistical impossibility—if everyone’s special, by definition no one is.

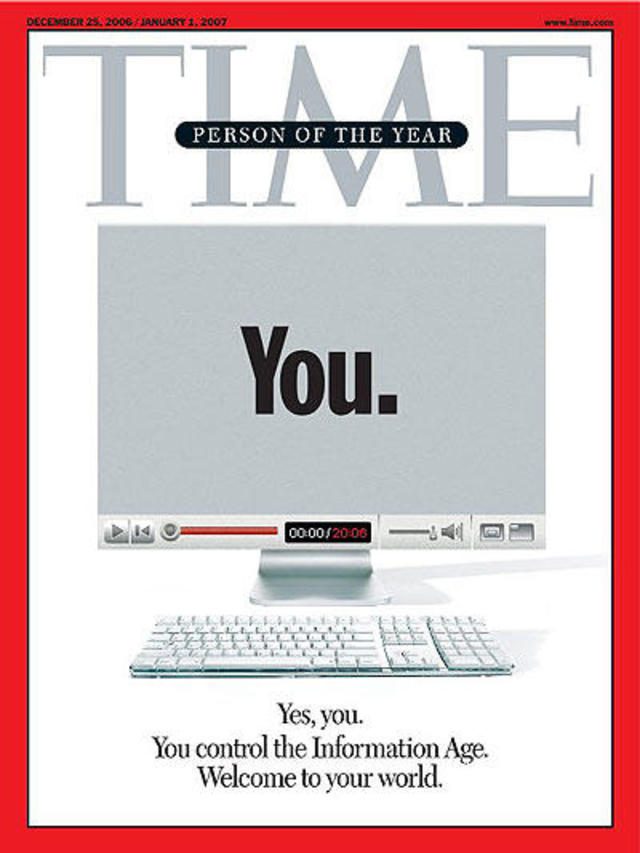

2006 Time’s Person of the Year

In 2006, however, everyone got the track-meet ribbon. Time’s Person of the Year was, simply: You. “You. Yes, You,” the cover line read. “You control the information age. Welcome to your world.” The conceit of the story was that in an era of user-derived content, we were all now running the cultural show. “For seizing the reins of the global media,” Time wrote, “for founding and framing the new digital democracy, for working for nothing and beating the pros at their own game, TIME’s Person of the Year for 2006 is you.” To make sure that the congratulatory message got through, the cover included a piece of reflective Mylar—a hand mirror to match the self-adoration theme of the story.

The Selfie Generation

In the years since, the tidal wave of first-person love has only climbed higher. Our careful curation of our Facebook pages has become something of a cultural art form, as we post only the prettiest pictures, the sunniest news, the funniest observations—grooming our image for a following that we convince ourselves gives a hoot. We have become artists of the selfie, the first-person photo taken with a smartphone held at arm’s length—an immediately recognizable posture that may become the signature pose of our era. The Vine website allows us to post eleven-second video clips—the visual equivalent of Twitter—doing whatever we’ve convinced ourselves the world wants to watch us doing.

Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD)

It is much the same way with narcissism. The actual incidence of true narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) is just 1 percent in the general population, sneaking up to 3 percent in certain groups—such as people in their twenties who have yet to be humbled a bit by the challenges and setbacks of adult life. The numbers climb much higher among self-selected populations of people who have already entered psychotherapy for some emotional condition, ranging anywhere from 2 percent for the average therapy patient to 16 percent for institutionalized patients.

The behaviors that characterize the narcissistic personality are spelled out starkly by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), psychology’s universally relied-upon field guide to the mind, which defines the condition as, in effect, three conditions:

- a toxic mash-up of grandiosity,

- an unquenchable thirst for admiration and

- a near-total blindness to how other people see you

- a lack of empathy in the narcissist—an utter inability not only to understand what other people are feeling but how they may be responsible for those feelings, especially when they’re bad.

Bottomless appetite as well—for recognition, attention, glory, rewards.

“Narcissists are afflicted with a bottomless appetite as well—for recognition, attention, glory, rewards. And it’s a zero-sum thing. Every moment a narcissist spends listening to another party guest tell a story is a moment in which the stage has been surrendered. Most people welcome that give-and-take; it’s the social part of socializing, and listening can provide a welcome break from the performance demands of telling a story or otherwise holding court. In the karaoke cycle that is life, we all get our turns on the stage and our turns in the crowd. The narcissist withers in—and rages against—any dying of the light.

Egosyntonic

Personality disorders are among the most stubborn conditions psychologists treat, because they’re what is known as “egosyntonic”—which is shrink-talk for the idea that the patients buy into what their minds are telling them. You’re not paranoid, people really are after you; you’re not pathologically rigid, there really are certain ways all things must be done at all times; and you’re not narcissistic, you really are more talented, more important and just plain better than everybody else.

Egodystonic

Anxiety conditions, such as phobias and OCD, are what’s known as “egodystonic.” The person with a morbid fear of spiders or snakes or elevators knows it’s nuts but can’t control it. The obsessive-compulsive who devotes three hours a day to hand-washing or checking to make sure the stove is turned off recognizes the madness of the behavior and would much rather be doing other things, but the psychic pull of the rituals is too great.

“When anxiety sufferers come into therapy, they deeply want to change. When people with a personality disorder at last enter treatment, it’s typically because family or friends push them there.”

Narcissists thrive when there’s an opportunity for glory but are uninterested in the collaborative work that leads to greater good for a larger group; they bristle and bitch when their talents are challenged, but never consider the possibility that those talents may be less than they believe them to be or that there is at least room for improvement. For narcissists, setbacks are not opportunities to learn; they’re problems caused by somebody else who got in their way or sabotaged their plans.

Social Media

Social networking Web sites are built on the base of superficial ‘friendships’ with many individuals and ‘sound-byte’ [sic] driven communication between friends (i.e., wallposts),” the authors patiently explained. “A Facebook page utilizes a fill-in-the-blank system of personalization. All pages share common social characteristics, such as links to friends’ pages . . . and an electronic bulletin board, called the wall. . . . Many users have hundreds or even thousands of ‘friends.’

Narcissism in the Workplace

The workplace has never been a democracy, and it wasn’t designed to be. Companies without a clear organizational chart and well-defined lines of power sound wonderfully collaborative, except for the fact that they almost always fail. An office needs a boss, and a boss, like it or not, is a monarch. As with monarchs, too, bosses come in all varieties—kind, benign, malign, monsters. There is little way of knowing which one you’ll get when the two of you shake hands and you accept a new job. But you’ll learn quickly—and if your boss is a narcissist, you’ll learn terribly, too.

Genius, clearly, is not the same as goodness, prestige is not the same as integrity, and the possession of power is no guarantee that it will be used with restraint—especially when narcissism is stirred into the mix, which it is with disturbing frequency.

Most narcissists manage their dysfunction well enough to stay just on the safe side of plausible deniability—what looked like verbal abuse was merely a needed employee reprimand; what the disgruntled subordinate claims was a stolen idea was actually one of many things the boss had been considering for a while.

The Peacock in the Oval Office

People come to the presidency in a lot of ways. There are princeling presidents—FDR, the younger Bush, John Kennedy, scions helped along by bloodlines and money to an office that most people consider out of reach.

There are scrapper presidents, people with humble—sometimes almost tragic—backgrounds who fight their way to the presidency and arrive there ebulliently (Bill Clinton), self-importantly (Jimmy Carter), eccentrically (LBJ), bitterly (Richard Nixon), but grab the prize all the same. There are happy presidents like Ronald Reagan; genial if awkward presidents like George H. W. Bush; war hero presidents like Andrew Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, Teddy Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower, men who have already been commanders once and decide that they enjoyed the experience so much they’d like to go right on running things, even if they have to do it in the drabber colors of civilian clothes.

Diffident people don’t get to the White House. Humble people don’t get to the White House. As surely as you have to be a natural-born citizen and at least thirty-five years old to seek the presidency at all, so too do you have to be a shameless, chest-thumping, unapologetic narcissist—however discreetly you might try to conceal that fact. That, history has shown, can be either a very good thing or a very bad thing, but it is, for better or worse, an unavoidable thing.

Diffident people don’t get to the White House. Humble people don’t get to the White House.

The narcissism of a tribe

Human beings are social creatures—a very important thing to be if soft, slow, fangless, clawless ground-dwellers like us were ever going to survive. But being social implies bands, and bands imply favoring your own above all the others. And since we’re rational creatures, too—creatures who like to feel good about ourselves and don’t like to think we seize land and resources and mates simply because we’re greedy—we tell ourselves that we favor our own kind because we’re smarter, prettier, better, more virtuous, more caring, a superior breed of people in a world filled with lesser ones.

“When a member of your group does something good, you attribute it to character,” says Yale University psychologist John Dovidio, who specializes in intergroup relationships, prejudice and stereotyping. “When they do something bad, you dismiss it as a situational deviation. We do the opposite with non–group members. Once you start categorizing people, you automatically feel more positive toward people in your group and some distrust for outsiders.

“Race is a conspicuous, unmistakable badge of difference—even if it ought to be an inconsequential one.”

Sport Tribalism

States may boast about their square mileage; cities may boast about their tallest skyscraper. But only in sports are there actually chants and merchandise making that point. Consider the “We’re number one” cheer rhythmically repeated by fifty thousand fans wearing giant foam rubber fingers.”

“It is hardly a novel observation that if war is politics by other means, sporting events are war by other means.”

Super Bowl Ad

COLLECTIVE NARCISSISM has its most circuslike expression in sports and its most deadly expression in war, but it has its most profitable expression in the marketplace—particularly in the case of advertising. We have created an entire industry devoted to the singular, self-adoring art of proclaiming that the thing you create, build and sell is better than anyone else’s, and companies are willing to spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to announce that fact in a newspaper or during a TV show. During the 2013 Super Bowl, a single thirty-second spot went for a stunning $3.5 million. That’s a lot to spend just to say you’re great.

| Year | Price of 30-second commercial |

| 2018 | $5,200,000 |

| 2019 | $5,300,000 |

| 2020 | $5,600,000 |

| 2021 | $5,500,000 |

“In a crowded marketplace, there is no better way to ensure sales than to have consumers stop asking questions the moment they see your name.”

Tomorrow Belongs to Me

It’s probably best for all of us to get used to narcissism and practice the art of dealing with it—recognizing the narcissistic lover before we become too entangled, the narcissistic boss before we take the job, the narcissistic politicians before we elect them to high office. And if we’re too late—if we realize that we’ve got a megalomaniacal monster on our hands only when the problems start occurring—we must similarly become adept at extricating ourselves. That may mean leaving the job with the narcissistic boss, shutting out the narcissistic coworker, firing the narcissistic lover, voting out the narcissistic pol.

No matter what, however, narcissism sure isn’t going anywhere. The disorder will remain part of the whole bestiary of humanity’s psychic maladies—depression, obsessions, phobias, paranoia, rage, addiction, delusions, dementia—that have always afflicted us and always will. Some have their value. In periods of depression can come reflection and insight. In obsessions can be focus; in paranoia, caution; in rage, self-assertion. A little bit of anything can shape and strengthen and anneal the personality. Too much can wreck it.

So, too, is it with narcissism. It’s not necessarily bad when self-confidence comes with blinders, shutting out worry and self-doubt, since that can be essential to succeeding in spite of pitfalls and long odds. But the blinders have to be removable. Charm, similarly, wins friends and followers; but it repels them if there’s nothing underneath it. Abiding love of the self is not only all right but essential, as the sad lives of the self-loathing show; but love of self to the exclusion of others produces its own kind of sorrow.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

2 Comments

Pingback: Top Quotes on Narcissism. | Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: On Narcissism. | Lanre Dahunsi