In his book, A Complaint Free World, Revised and Updated: Stop Complaining, Start Living, ordained minister and best-selling author, Will Bowen compares the frigatebird and the seagull bird in relationship to how we handle life situations. He writes:

When you do the things you need to do, when you need to do them, the day will come when you can do the things you want to do, when you want to do them.

American author, motivational speaker and leading authority on human potential, Zig Ziglar shared some great strategies for goal achievement in his book “Goals Take You to The Top!: How to Get What You Want”. As Ziglar often said “You can have everything in life you want, if you will just help other people get what they want.” Here are some of the tools, tips and strategies that he encouraged for goal attainment:

“If you aim at nothing you will hit it every time!” —Zig Ziglar

“The goal of recovery is learning self-care, learning to free ourselves from victimization, and not to blame ourselves for past experiences. The goal is to arm ourselves so we do not continue to be victimized due to the shame and unresolved feelings from the original victimization.”

Melody Beattie is an American author who writes on codependency and strategies for dealing with codependent relationships. Her books have helped shape my thought on codependency and provided tools for recovery, healing and self-care. Her books include: Codependent No More, Beyond Codependency, The New Codependency, and The Language of Letting Go.

“A codependent person is one who has let another person’s behavior affect them and who is obsessed with controlling that other person’s behavior.”

In her book, Codependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for Yourself, American author Melody Beattie shares the following illuminating thoughts on self-care.

“The middle ground of self-care lies between the two extremes of controlling others and allowing them to control us. We can walk that ground gently or assertively, but in confidence that it is our right and responsibility.” – The Language of Letting Go

Melody Beattie

“When others hold our pens, we live with a constant gnawing fear of their disapproval. Their feedback is no longer an indictment of our behavior; it is an audit of our worth.

In their insightful book, Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes are High, authors Joseph Grenny, Kerry Patterson et al write about “The Other Side Academy (TOSA) Game” and the concept of retaking one’s pen.

The Other Side Academy

The Other Side Academy is a training school in which students learn pro-social, vocational and life skills allowing them to emerge with a healthy life on “the other side”. Many of those who seek entrance into the Academy are convicts, substance abusers or homeless. TOSA teaches students both fundamental personal management and relationship skills such as keeping one’s promise, accountability, love, charity, and dependability.

“Nobody can go back and start a new beginning, but anyone can start today and make a new ending.” – Maria Robinson.

2025 is going to be a year of new beginnings, an opportunity to recaliberate and reset. It is ok to feel stuck, unsure, fall down, lose one’s way but the goal is to always bounce back, re-group and keep pushing. The new year is an opportunity to start afresh, set new goals, re-align commitments and decide to become who you instinctively know you were meant to be. As the saying goes “You don’t have to be great to get started, but you have to start to become great”. The bigger the goal, the bigger the struggle. Achieving your goal is not guaranteed but the struggle is guaranteed.

“You don’t have to be great to get started, but you have to start to become great”.

On your path to achieving your goal, you are going to stumble. Rest if you have to but don’t settle, or don’t dare give up on your dreams. You are put here specifically to discover your potential and awaken the giant within you. I know it is tough trying to pursue an audacious goal like finding your purpose in a world where you are expected to fit in with the crowd but please, give it shot. We miss all the chances we don’t take, begin anew and unleash your undiscovered potential. The best is yet to come and if you don’t try, you never know. You’ve got this.

“THE OLD MAN SAT DOWN on his favorite bench, settling in with his newspaper for his lunchtime ritual. He was a man of routine and could be found here most any day, enjoying the trees, the children playing, and the sounds of the bustling city around the park.

One day a young man sat down next to him with a paper of his own. The old man moved over a bit to make room, and went back to reading. After a few minutes, however, the new bench partner said, “Excuse me, sir?”

“Yes?” the old man answered, looking up with a friendly smile.

“Would you happen to have the time?” the younger asked.

The old man looked the young man over for a moment, taking in the fact that he was pleasant looking. “No,” he said, then went back to reading his paper.

Puzzled, the younger man could not imagine why the older man would not give him the time, having noticed that he was wearing a watch. So, he asked.

“Umm, excuse me, sir?”

“Yes?” the older one replied.

You don’t have to be great to start but you have to start to be great.

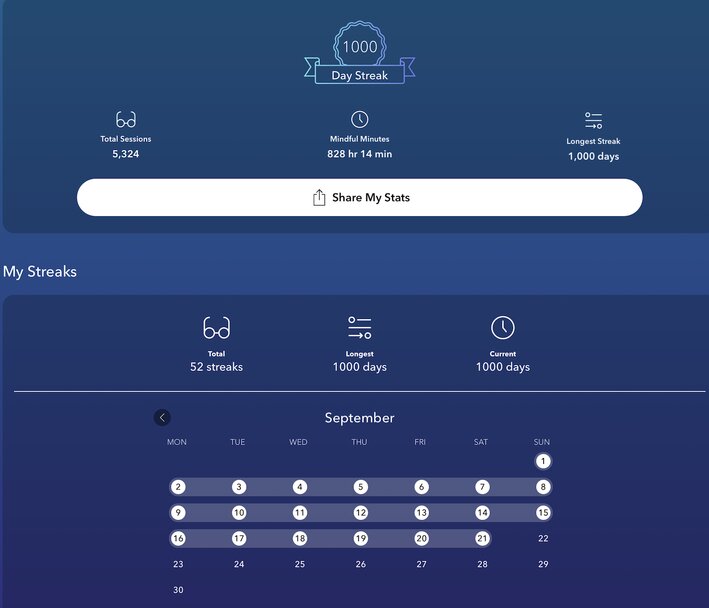

I have always heard of meditation from reading multiple non-fiction books but it is a practice, I hoped to start someday. But that changed in 2020 during the global COVID-19 lockdown; the rest they say is history. The lockdown was an anxious period for me and it was stressful with the uncertainty and rollercoaster of things happening in the world. I started meditating after watching a Lebron James calm advert on how meditation has helped him become a better basketball player and human. I am a Lebron fan and I am also obsessed with studying what makes great people thick. Lebron James has been on top of his game in the NBA for over 22 years and I was curious to get to know the backend that makes his frontend effortless. I started with the Train Your Mind with LeBron James calm session and I have been hooked ever since.

In his inspiring book, The Wealth Money Can’t Buy: The 8 Hidden Habits to Live Your Richest Life, Canadian author Robin Sharma describes a framework he termed “The PENAM Principle,” which is at the core of how we become who we are. PENAM is an acronym for the five forces that form our core beliefs, basic behaviours, daily habits, and the way we view the world. The five forces are our parents, environment, nation, association, and media.

“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.” – Martin Luther King, Jr.

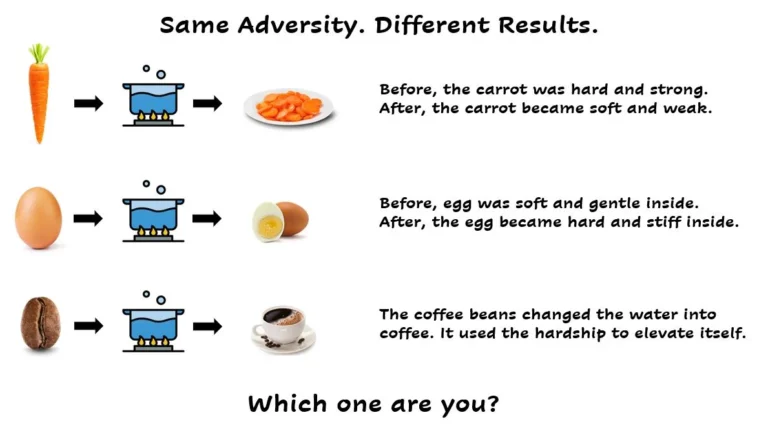

A young lady went home to visit her mother and told her about her life and how things were so hard for her. She was tired, upset, and annoyed at all these difficulties. Often, she wanted to run away or give up. Her mother listened empathetically, then took the daughter to the kitchen. She filled three pots with water and boiled the water.

She then put a carrot in the first pot, an egg in the second pot, and coffee beans in the third pot. After twenty minutes or so, she turned off the fire and put all three items in separate bowls.

She put these three bowls on the dining table and asked her daughter, “What do you see?”

Intrigued, the daughter replied, “A carrot, an egg, and coffee.”

The Museum of Failure is a touring exhibition that features a collection of failed products and services. It was inspired by its founder and curator, Samuel West, ‘s 2016 visit to the Museum of Broken Relationships in Zagreb, Croatia. The museum first opened on June 7, 2017, in Helsingborg, Sweden. According to the curator, the museum aims to help people recognize that “we need to accept failure if we want to progress” and encourage companies to learn more from their failures without resorting to “cliches.”

The Museum of Failure is a collection of failed innovations that we can learn from – Samuel West, curator and founder of the Museum of Failure

Buddhist meditation teacher and author Michael Stone developed an acronym-based model for working with strong emotions: SAIN 1—Stop, Allow, Investigate, Non-identification.

S: STOP

- It begins with stopping; how to meet the present moment with stillness without adding anything extra? When the tidal waves come, can you stop?

A: Allow or Accept

- To allow what’s moving through the body to fully arrive, to really feel it. You can’t allow something into awareness if you can’t stop.

I: investigate.

- Check it out. How is this showing up? Where is it showing up in my body? Ask every question, but why? Why is an invitation for the storyteller to get involved a move away from the body into abstraction? How to stay with physical sensations?

N: non-identification.

- When you have a stressful emotion show up, and you can stop, know what it is, and be curious about your experience, then you can arrive at the last step, which is to fully become the emotion. The shivering puddle. These steps are not just a way to work with negative emotions but also positive ones. When you’re really excited let the feelings come without identifying with them. Feelings are not I, me, mine. This is a recipe for getting closer and more intimate with experience.

SAIN 2 (in French it means health): Stop, Accept, Investigate, Non-Identification. Stop means recognizing that there’s a mood. Maybe you want to label it. Accept means allowing the mood to be there, instead of pushing it away, or allowing it to overtake you. Investigate means going into the body and seeing where the sensations are. What are the exact physical sensations and where are they? Non-identification is about becoming the energy, but not identifying with the energy. This is a practice that can be done anytime, you don’t have to wait for a tsunami of emotion to strike. In fact, without the preparation and steady practice in working with “smaller” moods, it’s hard to deal with the big swings.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

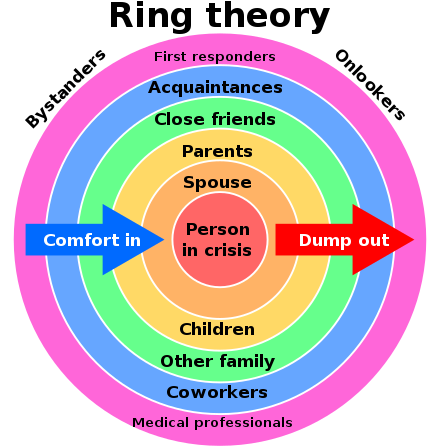

People who are suffering from trauma don’t need advice. They need comfort and support. So say, “I’m sorry” or “This must really be hard for you” or “Can I bring you a pot roast?” Don’t say, “You should hear what happened to me” or “Here’s what I would do if I were you.” And don’t say, “This is really bringing me down.”

The Ring Theory is a concept developed by clinical psychologist Susan Silk and her friend arbitrator Barry Goldman. They suggest an approach that helps with not saying the wrong things when trying to support someone dealing with a crisis or in a stressful situation. They site a perfect example of such an unintended insensitive remark in their article:

When Susan had breast cancer, we heard a lot of lame remarks, but our favorite came from one of Susan’s colleagues. She wanted, she needed, to visit Susan after the surgery, but Susan didn’t feel like having visitors, and she said so. Her colleague’s response? “This isn’t just about you.”

High-performance coach Brendon Burchard left a corporate consulting job in 2006 because he was not finding fulfilment in the outputs that were being rewarded. He chose to quit and set up his career as a writer, speaker and online trainer. He began creating content to inspire and empower others.

Like a lot of people new to the expert industry, I thought I had to figure out the writing industry, the speaking industry, the online training industry. I made the mistake of going to dozens of conferences to try to figure out each of the industries, without realizing that they all were the same career of being a thought leader and had similar outputs that mattered most.

Brendon made some mistakes starting out such as trying to figure out the industry by attending numerous conferences instead of doing the work and creating quality output. The frustration led to an epiphany which to focus on quality output. He realized that if he was going to become a professional speaker, his PQO would be the number of paid speaking gigs at a certain booking fee.

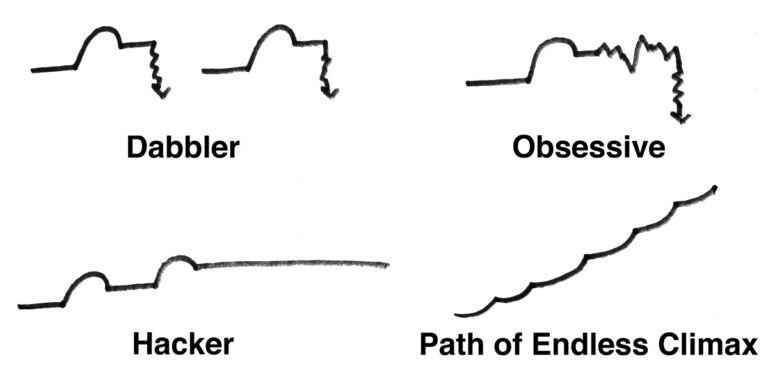

In his book, Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-Term Fulfillment, American writer George Leonard describes the learning paths to mastery. He writes: We all aspire to mastery, but the path is always long and sometimes rocky, and it promises no quick and easy payoffs. So we look for other paths, each of which attracts a certain type of person.

The Dabbler, the Obsessive, and the Hacker

SUCCESS makes you fearful, Of losing your place, Of gambling with stature, Of losing your face.

Bracken Darrell is the CEO of VF Corporation, an American global apparel and footwear company. In June 2023, Darrel was appointed CEO of VF Corp, the parent company of Vans sneakers and Timberland boots. Before his appointment, he was CEO of Logitech, a computer peripherals maker. As the CEO of Logitech, he penned a Seuss-like poem titled “The Secret to Success: Avoid It.” wherein he writes about the pitfalls of success.

In a LinkedIn post about the poem, Darrell quipped:

We all seek success, but the actual experience of thinking you’re successful is potentially performance eroding or even dangerous. That’s true for businesses, teams and us as individuals. In extreme cases, others think you are smarter, more creative, and more often right. You aren’t, of course. You’re the same woman or man as before.

In the poem, The Secret to Success: Avoid It, Darrell made the following observations about success and failure:

You joined the world naked, Unclothed and unhaired. You started out solo, Crying and scared.

By trial and error, You crawled up and past two, Then learned right through grade school, High School and Big U!

Sometimes you won, Oft you fell down destroyed, Broken and beaten, and, Worse, unemployed.

Sometimes you won, Oft you fell down destroyed, Broken and beaten, and, Worse, unemployed.

From that elevation, You tumbled down far, You rolled, bounced, and crumbled, You damaged your car.

You climbed up again though, Now humbled, strong willed, No, nothing could stop you, Not even a spill.

You learned to keep learning, As you grew older, When you lost you showed grace, You were humbler but bolder.

As the ‘wins’ piled up, A new friend joined you, too, At first you hardly took notice, But SUCCESS grew and he grew.

He praised average comments, Your most awkward charm, He loved all your faults, Like your worst throwing arm.

He praised average comments, Your most awkward charm, He loved all your faults, Like your worst throwing arm.

SUCCESS makes you fearful, Of losing your place, Of gambling with stature, Of losing your face.

So what now my friend, You see what SUCCESS brings, How does one avoid him, Yet accomplish great things?

You’ve got someone to nurture, Still naked, no hair, That someone is yours, ONLY yours, so take care!

One vulnerable child, Lives lifelong in us all, His name is ‘Potential’, He stands ten feet tall.

SUCCESS is wicked, He’s not what he seems, He lunches on goals, For dinner eats dreams.

And I hope if you live To 120 plus 4, You read this each year, Feel it down in your core.

Remember Success Is the wolf in your tale, Live hungry in life, Always learn and please fail.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.