You become a writer by writing. There is no other way.

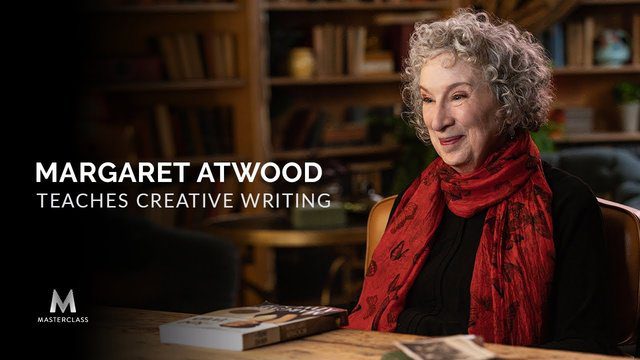

Margaret Atwood is the author of more than 40 books of fiction, poetry, and critical essays. Her latest book of short stories is Stone Mattress: Nine Wicked Tales (2014). Her MaddAddam trilogy— the Giller and Booker prize-nominated Oryx and Crake (2003), The Year of the Flood (2009), and MaddAddam (2013)—is currently being adapted for HBO. The Door (2007)is her latest volume of poetry. Her most recent nonfiction books are Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth (2007) and In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination (2011).

Her novels include The Blind Assassin (2000), winner of the Booker Prize; Alias Grace (1996), which won the Giller Prize in Canada and the Premio Mondello in Italy; The Robber Bride (1993): Cat’s Eye (1988): The Handmaid’s Tale (1985),now a TV series with MGM and Hulu: and The Penelopiad (2005).

Atwood’s works encompass a variety of themes including gender and identity, religion and myth, the power of language, climate change, and “power politics”. Atwood is a founder of the Griffin Poetry Prize and Writers’ Trust of Canada. She is also a Senior Fellow of Massey College, Toronto.

Atwood is also the inventor of the LongPen device and associated technologies that facilitate remote robotic writing of documents. Margaret lives in Toronto with writer Graeme Gibson.

If you really do want to write, and you’re struggling to get started, you’re afraid of something. What is that fear?

Here are my favorite takeaways from viewing

Early Reader/Writer Margaret became a writer because she was an avid and early reader. As a child she wrote comics and little stories, and founded a puppet troupe in junior high. She began writing seriously when she was 16 years old. Atwood’s Writing Process Margaret starts by handwriting because she finds it generates a flow from her brain to her hand to the page. Then she transcribes these pages to typed ones, editing as she goes in a “rolling barrage” method that allows her keep what she’s just written fresh in her mind. She waits until she has about 50 or 60 pages before she begins to think about structure. Margaret describes her own process as “downhill skiing”: she writes as fast as she can, and then goes back later to revise (to literally re-“vision”) what she’s got down. The wastepaper basket is your friend A story needs a break in a pattern to get it going. Every story is made up of both events and characters. A story happens because a pattern is interrupted. If you are writing about a day that is like any other day, it is most likely a routine, not a story. On Structure: Writing is a way of recording the human voice. Who Tells the Story: Narrative Point of View One way to determine what point of view strategy to use in your novel is to ask: Whose voice is telling the story? To whom are they telling it, and why? Characterization If you are writing from the point of view of a character who is unlike you in some way— identifies as a different gender, for instance— Margaret recommends you run your story by someone who shares your character’s traits for accuracy On Writing You become a writer by writing. There is no other way. Crafting Dialogue If you’re going to have your characters talking to one another, it should be for some reason, not just to have them chattering away. Sensory Imagery It is concrete if it appeals to one of the five senses, and it is significant if it carries an idea or judgment, or reveals something about a character. – Janet Burroway Prose Styles: Baroque vs Plainsong Writing If you’re a writer interested in writing a book that finds a public readership, you’re always contending with readers’ expectations, and deciding at each turn how much your book will fulfill or frustrate those expectations. Forget Genre, Make Me Believe It Forget Genre, Make Me Believe It On Research There are no guarantees in the world of art. Your Ideal Reader Recommended Resources MasterClass is a streaming platform that makes it possible for anyone to learn from the very best. MasterClass is an online membership – accessible on your phone, web, Apple TV, Roku devices, and Amazon Fire TV – that offers classes on a wide variety of topics taught by 85+ world-class masters at the top of their fields. Their immersive learning experiences combine incredible video content, downloadable materials, and social interaction with the MasterClass community, all of which users can explore at their own pace. The annual membership is available for $180 USD, which allows unlimited access to ALL on demand MasterClass content for the year Margaret Atwood Teaches Creative Writing Give One Annual Membership. Get One Free. All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion. For More Information: MasterClass Home Page

Don’t be afraid to try out different techniques, voices, and styles. Keep what works for you and discard the rest. Your material and process will guide you to your own set of rules.

1 Comment

Pingback: Lessons Learned from David Baldacci’s Masterclass Session on Mystery and Thriller Writing. – Lanre Dahunsi