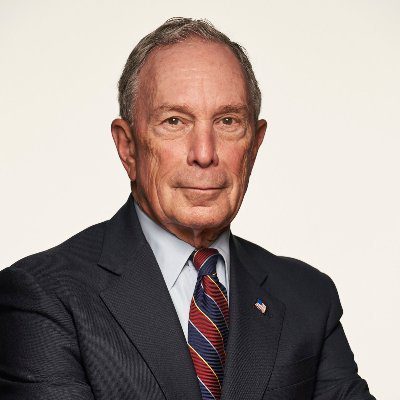

Michael Bloomberg is the majority owner and co-founder of Bloomberg L.P. He was a three-term New York City Mayor from 2002 to 2013 and was a candidate for the 2020 Democratic nomination for the United States president. According to Forbes, Bloomberg is the 16th-richest man globally, with a net worth of $USD 59 billion as of March 13, 2021.

He got his start in 1966 on Wall Street at the securities brokerage Salomon Brothers selling stocks. He rose to become a general partner at the firm but was fired in 1981, after Phibro Corporation bought Salomon Brothers. Bloomberg was paid $10 million for his equity stake in Salomon Brothers, and he used the windfall to start his firm Bloomberg L.P.

Bloomberg L.P. is a privately held financial, software, data, and media company headquartered in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The firm is known for its Bloomberg Terminal. The company has 167 locations and nearly 20,000 employees.

“There are many reasons why some succeed and others don’t, why some just continue to grow and others spurt up and, as quickly, collapse. Three things usually separate the winners from the losers over the long term: time invested, interpersonal skills, and plain old-fashioned luck.”

Bloomberg Terminal

The Market Master terminal, later called the Bloomberg Terminal, was released to market in December 1982. Merrill Lynch became the first customer, purchasing 20 terminals and a 30% equity stake in the company for $30 million in exchange for a five-year restriction on marketing the terminal to Merrill Lynch’s competitors.

In his Book, Bloomberg by Bloomberg, Micheal writes about some of the keys to his success in business and in life. He chronicles his life at wall street, getting fired, starting over at 39, the entrepreneurial journey, becoming a politician, his family life, and his outlook on life.

Starting over at 39

I had spent my first twenty-four years getting ready for Wall Street. I had survived fifteen more years before Salomon Brothers threw me out. At age thirty-nine, the third phase of my life was about to start. With whatever values my parents had taught me, $10 million in my pocket, and confidence based on little more than bruised ego, I started over.

Rebel

When we started the company in a small room on Madison Avenue, we were refugees from Wall Street motivated by an idea that we could build something new that just might make a difference in the world of finance. People told me I was crazy to think we could overturn the status quo on Wall Street and challenge the giants of financial information.

Maybe I was. But within a few years, we had our first customer. And from an initial bond product, we branched out into stocks, commodities, and news. We added magazines, radio, and television—all built upon the mountain of data and information generated by the Terminal and demanded by the world’s most influential business and financial professionals. Before the Internet existed, we had created the world’s most powerful intranet. And before the phrase “social network” came to be, we had created one for the financial services industry.

The Thrill of Getting Fired

Was I sad on the drive home? You bet. But, as usual, I was much too macho to show it. And I did have $10 million in cash and convertible bonds as compensation for my hurt feelings. If I had to go, this was the time. I was getting my money out of the firm then instead of ten years later. With Phibro paying a merger premium, I was doubling my net worth. Since somebody else had made the decision, I’d even avoided agonizing over whether to stay at Salomon—a timely question, given my then-declining prospects in the company.

Afterward, I didn’t sit around wondering what was happening at the old firm. I didn’t go back and visit. I never look over my shoulder. Once finished: Gone. Life continues!

Most fortunes are built by entrepreneurs who started with nothing and generally got fired once or twice in their careers. And throughout history, the vast majority of great writers, artists, musicians, dancers, jurists, and athletes have come from the less financially secure families. The CEOs of many Fortune 500 companies went to State U rather than Ivy League schools. Could it be that good “prenatal intelligence” (the ability to pick the right parents) is possessed by those born into poor families as opposed to those who are children of the rich? Or that the traditional prerequisites of success are not terribly important today?

History repeats itself

I developed a sense of history and its legacy, and remain amazed at how little people seem to learn from the past; how we fight the same battles over and over; how we can’t remember what misguided, shortsighted policies led to depression, war, oppression, and division. As citizens, we continually let elected officials pander for votes with old, easy, flawed solutions to complex problems. As voters, we repeatedly forget the lessons of others who didn’t hold their chosen officials accountable. God help us if George Santayana was right and we’re doomed to repeat it all again.

In fact, although many Harvard relationships helped me, almost none were with those who impressed me so much back then.

Hustlers Mentality

But I came from a background where none of those class distinctions mattered. I didn’t know better, and I wouldn’t have understood if someone had tried to explain the social niceties. I grew up with the civics-class traditional American ethic, with my parents as role models: Work hard, value education, and do things yourself, whether the labor was mental or physical. For me, with college loans to pay off, a good job was a good job. And, as I would learn later on in my life—at Salomon Brothers and in my own company—it’s the “doers,” the lean and hungry ones, those with ambition in their eyes and fire in their bellies and no notions of social caste, who go the furthest and achieve the most.

it’s the “doers,” the lean and hungry ones, those with ambition in their eyes and fire in their bellies and no notions of social caste, who go the furthest and achieve the most.

SHOWING UP

“I’ve never understood why everybody else doesn’t do the same thing—make himself indispensable on the job. That was exactly what I did during the summer between my first and second years in graduate school, when I worked for a small Harvard Square real estate company in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Students would come to town just to find an apartment they could move into in September; they were always in a rush, eager to get back to their vacations as soon as possible. We ran generic advertisements in the newspapers for three or four different sizes of rentals; each ad would fit twenty of our apartment listings. Every day, the newly arrived would-be renters got up early, grabbed the newspaper at their hotels, looked at the real estate section, made a phone call, scheduled an appointment with “the next available agent” to see housing that sounded appropriate, and went back to bed. Later in the day, they’d go out and actually look.

“I went to work at six-thirty in the morning. By seven-thirty or eight o’clock, all potential renters visiting Cambridge had called our company and booked their apartment-viewing visits with whoever was there. I, of course, was the only one who bothered to come in early to answer the phone: The Adult “professionals” who worked for this company (I was “the summer kid”) started work at nine-thirty. Then, all day long, they sat in wonderment as person after person walked into the office asking for Mr. Bloomberg.”

It’s said that 80 percent of life is just showing up. I believe that. You can never have complete mastery over your existence. You can’t choose the advantages you start out with, and you certainly can’t pick your genetic intelligence level. But you can control how hard you work. I’m sure someone, someplace, is smart enough to succeed while “keeping it in perspective” and not working too hard, but I’ve never met him or her. The more you work, the better you do. It’s that simple. I always outworked the other person (and if I hadn’t, he or she would be writing this book).

INCREMENTAL PROGRESS

“Life, I’ve found, works the following way: Daily, you’re presented with many small and surprising opportunities. Sometimes you seize one that takes you to the top. Most, though, if valuable at all, take you only a little way. To succeed, you must string together many small incremental advances—rather than count on hitting the lottery jackpot once. Trusting to great luck is a strategy not likely to work for most people. As a practical matter, constantly enhance your skills, put in as many hours as possible, and make tactical plans for the next few steps. Then, based on what actually occurs, look one more move ahead and adjust the plan. Take lots of chances, and make lots of individual, spur-of-the-moment decisions”

THERE ARE NO GUARANTEES

Don’t devise a Five-Year Plan or a Great Leap Forward. Central planning didn’t work for Stalin or Mao, and it won’t work for an entrepreneur either. Slavishly follow a specific step-by-step strategy, the process gurus tell you. It’ll always work, they say. Not in my world. Predicting the future’s impossible. You work hard because it increases the odds. But there’s no guarantee; much is dependent on what cards happen to get dealt. I have always believed in playing as many hands as possible, as intelligently as I can, and taking the best of what comes my way. Every significant advance I or my company has ever made has been evolutionary rather than revolutionary: small earned steps—not big lucky hits.

LOVE WHAT YOU DO

Then, whatever your idea is, you’ve got to do more of it than anyone else—a task that’s easier if you structure things so that you like doing them. Since doing more almost always leads to greater accomplishments, in turn you’ll have more fun. And then you’ll want to do even more because of the rewards. And so on. I’ve always loved my work and put in a lot of time, which has helped make me successful. I truly pity people who don’t like their jobs. They struggle at work, so unhappily, for ultimately so much less success, and thus develop even more reason to hate their occupations. There’s too much delightful stuff to do in this short lifetime not to love getting up on a weekday morning.

Be Kind

Someone once said, “Be nice to people on the way up; you’ll pass the same ones on the way down.” I believe in treating associates well, but not for that cynical reason: Having been both up and down repeatedly, my experience says you pass different people as you go through the inevitable cycle.

Happinness

Think about the percentage of your life spent working and commuting. If you’re not content doing it, you’re probably pretty miserable with the situation. Change it! Work it out with those next to you on the production line. Talk to your boss. Sit down with those you supervise. Alter what’s in your own head. Do something to make it fun, interesting, challenging, exciting.

You’ve got to be happy at your job. Sure, being able to feed the kids is the first focus. But when layoffs and promotions are announced, those with surly looks on their faces, those who always try to do less, those who never cooperate with others get included in the layoffs and miss the promotions. This big part of your life affects you, your family, society, and everything else you touch.

Just Do It

If you’re going to succeed, you need a vision, one that’s affordable, practical, and fills a customer need. Then, go for it. Don’t worry too much about the details. Don’t second-guess your creativity. Avoid overanalyzing the new project’s potential. Most importantly, don’t strategize about the long term too much.

Planning

Don’t think, however, that planning and analysis have no place in achieving success. Quite the contrary. Use them, just don’t have them use you. Plan things out and work through real-life scenarios, selecting from the opportunities currently available. Just don’t waste effort worrying about an infinite number of down-the-road possibilities, most of which will never materialize.

Writing out your plans

Think logically and dispassionately about what you’d like to do. Work out all steps of the process—the entire what, when, where, why, and how. Then, sit down after you are absolutely positive you know it cold, and write it out. There’s an old saying, “If you can’t write it, you don’t know it.” Try it. The first paragraph invariably stops you short. “Now why did we want this particular thing?” you’ll find yourself asking. “Where did we think the resources would come from?” “And what makes us think others—the suppliers, the customers, the potential rivals—are going to cooperate?” On and on, you’ll find yourself asking the most basic questions you hadn’t focused on before taking pen to paper.

“If you can’t write it, you don’t know it.”

Baby Steps

When I saw that screen light up that day in the Merrill Lynch offices, I lost any residual doubt that Bloomberg could make it. We had picked just the right project. It was big enough to be useful, small enough to be possible. Start with a small piece; fulfill one goal at a time, on time. Do it with all things in life. Sit down and learn to read one-syllable words. If you try to read Chaucer in elementary school, you’ll never accomplish anything. You can’t jump to the end game right away, in computers, politics, love, or any other aspect of life.

The difference between stubbornness and having the courage of conviction sometimes is only in the results.

Giants are easy to beat

In fact, we would have had a much tougher time had we entered an industry that had lots of small, scrappy competitors. But we went against giants, and giants are usually easy to beat. Remember the Germans and then the Japanese versus Detroit’s “Big Three” automakers? If you have to compete based on capital, the giant always wins. If you can compete based on smarts, flexibility, and willingness to give more for less, then small companies like Bloomberg clearly have an advantage. The world changes every minute, and you forget that at your peril.

Dogma

Too often, people do things automatically, thoughtlessly. It has nothing to do with their inherent intelligence. It has everything to do with their inquisitiveness. Our schools too often fail to teach logic and skepticism. We are taught facts and techniques, not concepts and thoughts; we learn to accept, not question. This terrible failing in our educational system penalizes students for the rest of their lives.

Lack of consistency

Lack of consistency is another common failing that hurts us. People say, “We’ll always go in this direction,” but when they are faced with a real-life situation, they often act independently of their previous plans. Either their original resolution wasn’t well thought out, or they just don’t have the intellectual honesty to do what they said they’d do.

Ambition + Hardwork + Luck

You are born with a certain genetic intelligence level. Given the current state of medical science, you’re probably stuck with whatever God gave you. Nor can you change much of your environment in any practical sense. But does that mean you should give up? Sit back and just accept the hand you’ve been dealt? No, of course not. Ambition and hard work, mixed with luck, can carry you a long way.

Hardwork

The rewards almost always go to those who outwork the others. You’ve got to come in early, stay late, lunch at your desk, take projects home nights and weekends. The time you put in is the single most important controllable variable determining your future. You can try to beat the system by winning the lottery, but the odds are terrible. You can hope the government tries to equalize with Robin Hood tax policies and throws some money your way. The Communists tried to eliminate any form of meritocracy for seventy years and, in addition to wrecking their economies, they starved millions of people to death in the process.

If you put in the time, you aren’t guaranteed success. But if you don’t, I’m reasonably sure of the results.

Luck

If I had not gotten thrown out of Salomon Brothers, I’d never have founded our company. If I’d been thrown out later, the opportunity to compete against those distracted growing giants would have been less, and our success would probably have been diminished. Suppose I hadn’t been accepted at Johns Hopkins or Harvard Business School, or met Sue, or found just the right people to work at Bloomberg, or had the same college friends, or safely landed that helicopter or that plane. My life would be very different.

Work hard. Share. Be lucky. Then couple that with absolute honesty. People are much more inclined to accept and support someone they think is “on the level.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

1 Comment

Pingback: The Gift of getting fired. – Lanre Dahunsi